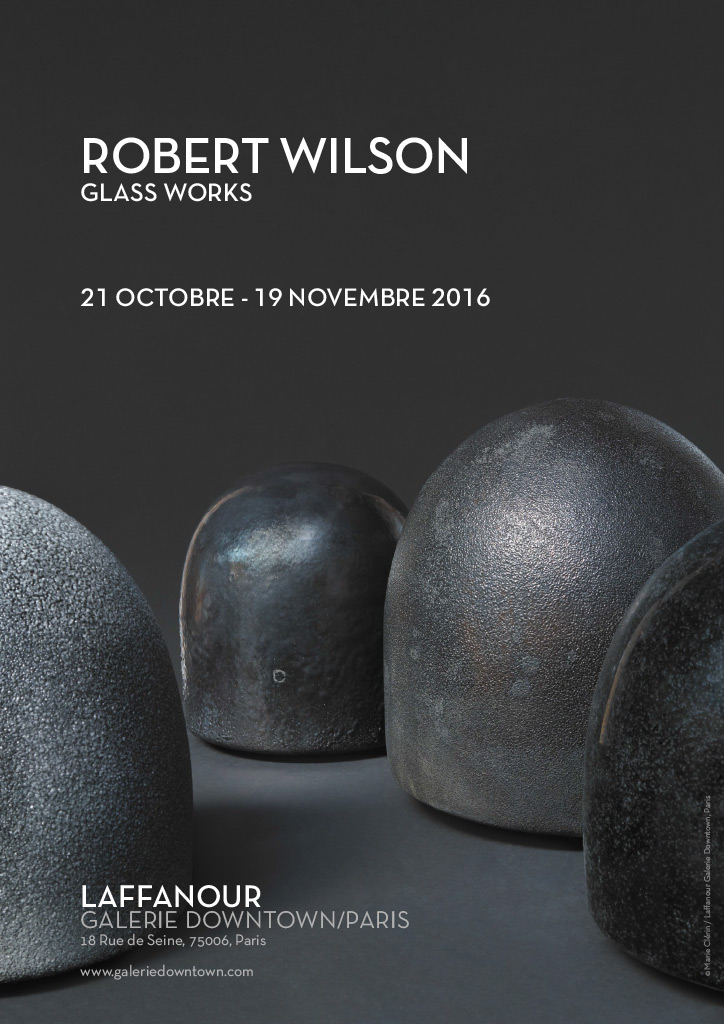

BOB WILSON, Glass works

“Robert Wilson passionate about glass…, eager to try it…”. This is what I learned in 1994 from a message from Paula Cooper, contacted for another project.

Robert Wilson occupies a very first place in the pantheon of artists who, at the beginning of the 70’s, changed the look of a generation in France, and that well beyond the theater. Along with Trisha Brown, he was one of the first significant contacts we had with the American avant-garde.

Invited by Jack Lang in 1971, he created “Le Regard du Sourd” in Nancy, a seven-hour show presented a few months later in Paris. For my part, it was in Annemasse that I discovered him in 1974 with “Lettre à la Reine Victoria”. It was two years after the “Documenta de 72”. The intellectual and emotional shocks felt in Kassel found in the dreamlike dimension of time and space proper to his universe a mysterious and fascinating inner resonance. In 1976, in Avignon, it was the dazzling of “Einstein on the Beach” and, since then, and until today, so many unforgettable creations that never cease to surprise where, as it is the case for an old friend, we thought we already knew everything. For if Bob Wilson is the master of the simplest structures, he is also the master of variations, of the infinite nuances that can be brought to them, of the subtle alliance of opposites and reversals, which we will see in his work with glass.

When I learned that Bob Wilson was interested in glass to the point of wishing to confront it, I was very surprised and I hastened to tell him that, whatever he wished to do, and even if he had no idea, the CIRVA would be happy to put itself at his disposal without reserve. For more than ten years, from 1994 to 2005, he assiduously attended the workshop, as much as his constant travels to the four corners of the world allowed him, for a few days, a weekend, sometimes almost a week, and that once or twice a year. All the pieces were made in his presence and if they came out of the kiln after his departure, without him having been able to see them, he would discover them on his return, directing the finishing to the last detail, the cutting, the polishing, the surface treatment. Finally, when they were all together, he examined them at great length before deciding whether or not to keep them.

Before coming to Marseille, he had had the opportunity to see Lino Tagliapietra, the most famous master glassmaker in the world from Murano. He admired his extraordinary virtuosity, and appreciated the lightness and tension of the forms he had created, which today are copied without reservation as if they had always been part of Murano’s heritage. The precision of Lino’s gestures and movements, combined with his extreme concentration, had so impressed Bob Wilson that sometimes he liked to imitate him, making his interlocutor hear in a flash where his connivance with the maestro lay.

Lino Tagliapietra came regularly to work at CIRVA. His collaboration was an immense joy for our small team as well as for the guest artists, and an infinitely precious support.

Bob Wilson’s first work sessions saw the meeting, full of mutual respect, of two “sacred monsters” coming from apparently very different fields. Facing the ovens, Lino’s kingdom, Bob had planted his sketch board. Armed with colored oil pastels, he drew vases or, more precisely, swirls of lines which, around an invisible axis, concentrated the energy of spirals that ended up forming a body.

For Bob Wilson, dance is at the heart of life as well as of his work. Observing the movements of Lino and his assistants, their incessant comings and goings from the kiln to the bench, which drew an invisible arabesque on the floor, the movements of the cane swung in space, raised, then lowered before being handed over to the maestro sitting at his blowing bench to be able to turn the glass gob horizontally, the gestures, incomprehensible for a layman, the gestures of his hand, caulked with wet paper or extended with wooden or metal tools, the moments of waiting and immobility that suddenly break the extreme vivacity of the tempo, the repetition of the same gestures, finally, everything in this ballet, carried Bob Wilson to appropriate this unknown material, through gesture and movement.

With his first drawings, a whirlwind of lines generating a form as if sui generis, no doubt he thought he could transcribe directly into the material the energy emanating from this great mechanism. He did not realize that each of these precise gestures was inscribed with the same precision in the material without leaving any room for spontaneity. He was unaware that introducing freedom into this perfectly regulated process was not the only way to make the work of art.