LE CORBUSIER, AN ART OF SYNTHESIS

As much in his architecture, his paintings, and his sculpture, as in his writings, Le Corbusier sought harmony, a form of synthesis of the arts. “Are not a picture, a sculpture, a house, a palace, a city made in any way of small pieces of matter and threads of one and the same occupation of the mind?” (1948)Home Equipment

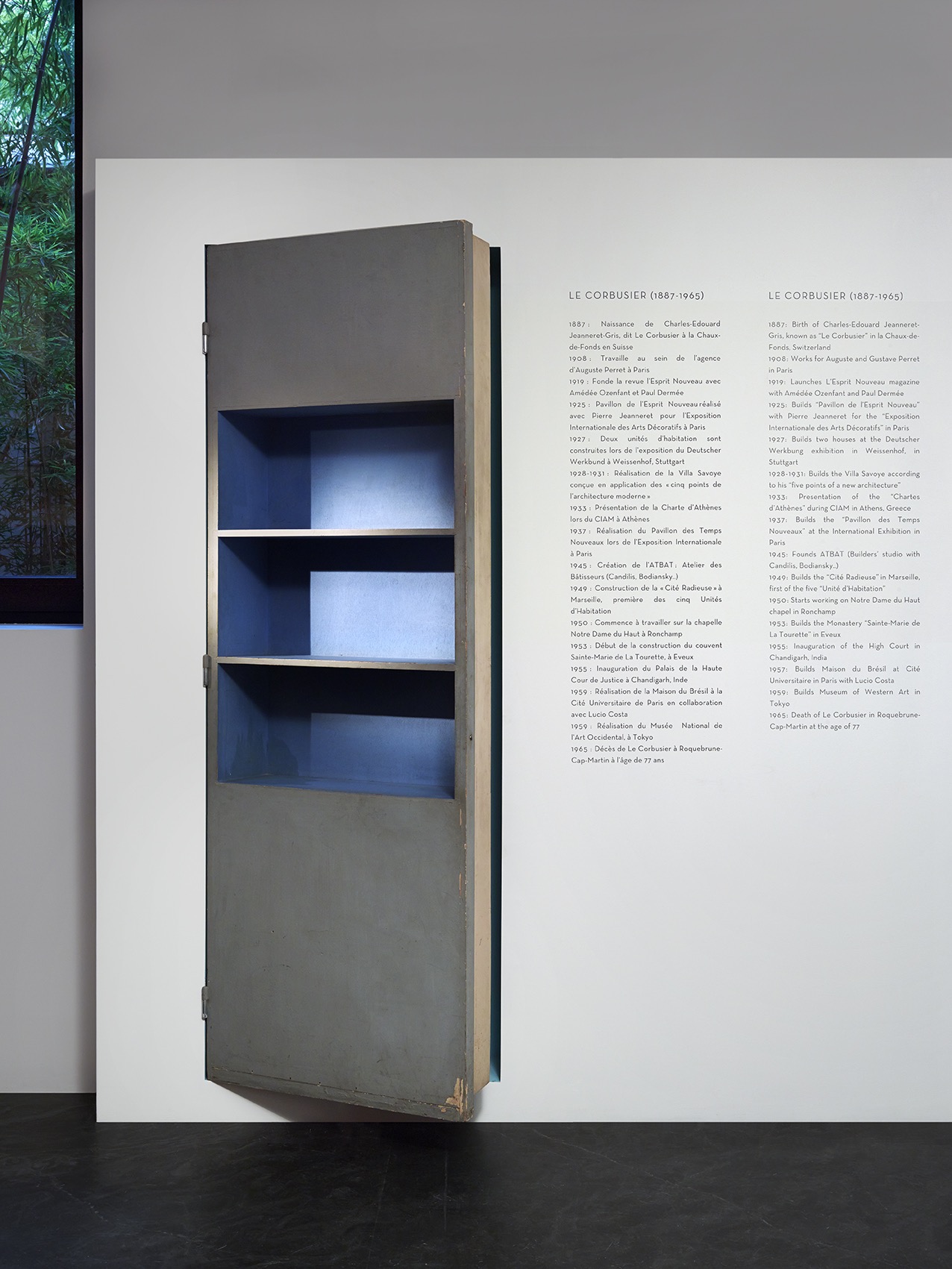

He then thought about the installation of the dwelling, and in no time came up with the idea of a commercial company which would sell all the elements of home equipment. They would be mass produced, to standard measurements, to meet the many different needs of a rational set of furbishings: windows, doors, standard racks serving as cupboards and forming part of the partition walls… The Citrohan No 2 House, the model of which was exhibited at the 1922 Autumn Salon, was the first complete prototype of the “machine à habiter”. Le Corbusier declared: “There is nothing shameful about having a house which is as practical as a typewriter”.

“Furniture is a servant”, he announced, seven months before he met Charlotte Perriand. He had sketched out “the different ways of sitting which seats had to be adapted to”. He drew his ideas from the range of Maple & Co. furniture and Thonet seats, which he regarded as standard objects; and he also drew inspiration from technical furniture for sick and injured people in his “sitting machines” programme. He drew up the basic diagrams. When she joined Le Corbusier’s agency in 1927, Charlotte Perriand took up the theoretical programme “of racks, chairs and tables” developed since 1924 with Pierre Jeanneret. “Le Corbusier expected me to give life to furniture”. Le Corbusier provided the avenue of research, then she took charge of producing the plans and making the equipment.

The history of the lounge chair conveyed the master’s approach. First of all, he set about studying William Morris’s chaise longue/easy chair, then Dr. Pascaud’s “Surrepos” chaise longue, all tentative research; Charlotte Perriand then finalized the studies and drawings, so the work involved a collaborative method. Le Corbusier devised and drew up the programme with Pierre Jeanneret; he was the investigator, while Charlotte Perriand was indisputably the kingpin. The programme “of chairs and tables” was finalized in the autumn of 1928, while the racks, the last element of Le Corbusier’s trilogy, were still on the drawing board. Charlotte Perriand designed them in metal, borrowing the concept of the wooden racks created in 1925 by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, for the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion. For publicity purposes, the Thonet company financed the first exhibition of the programme L’équipement intérieur d’une habitation in an area of 100 sq. m./1,100 sq.ft, at the Salon d’Automne in December 1929. She provided the racks and found herself associated with all the publications mentioning the furniture… It was a period of struggle and involvement. The mass-produced edition would finally be taken on by Thonet. The furniture was also designed for private homes, as part of the architecture programme.

Immediately after the war, Le Corbusier finally achieved his vision of the vertical city (1945-1952) with the Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles. The apartments with their double east-west orientation, arranged on two levels, had a double-height living room, while the furnishings were carefully designed to rationalize the space. Charlotte Perriand was once more called upon for the cell-type furniture (1947) and the kitchen, (1947-49). She presented the whole thing at the Salon des arts ménagers (household arts) in the “Habitation” section in 1950. The roof terrace proposed collective furnishing, children’s gardens, and swimming pools.

The notion of “standards” was probably the greatest innovation made by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perriand, perfectly adapted to requirements. Paradoxically, their origin lay in the classical tradition and the anonymous production of popular arts and crafts.

Anne Bony, October 2015

Translation Simon Pleasance