Koreanisms by Olivier Gabet

These days, Korea matters. We can no longer sidestep this fact, we can no longer ignore this country’s masterful contribution to the history of a modernity which is being written today on a world scale, a history which likes juggling with vital -isms– Orientalism, Japonism, Africanism, primitivism, and the like– to express the permanent curiosity of the way people look at things in other places, and their likes and dislikes. It is now important to offer a place of choice to Korea, and to Korean artists and creators: Koreanism, like a new movement up for examination, another phenomenon to be defined.

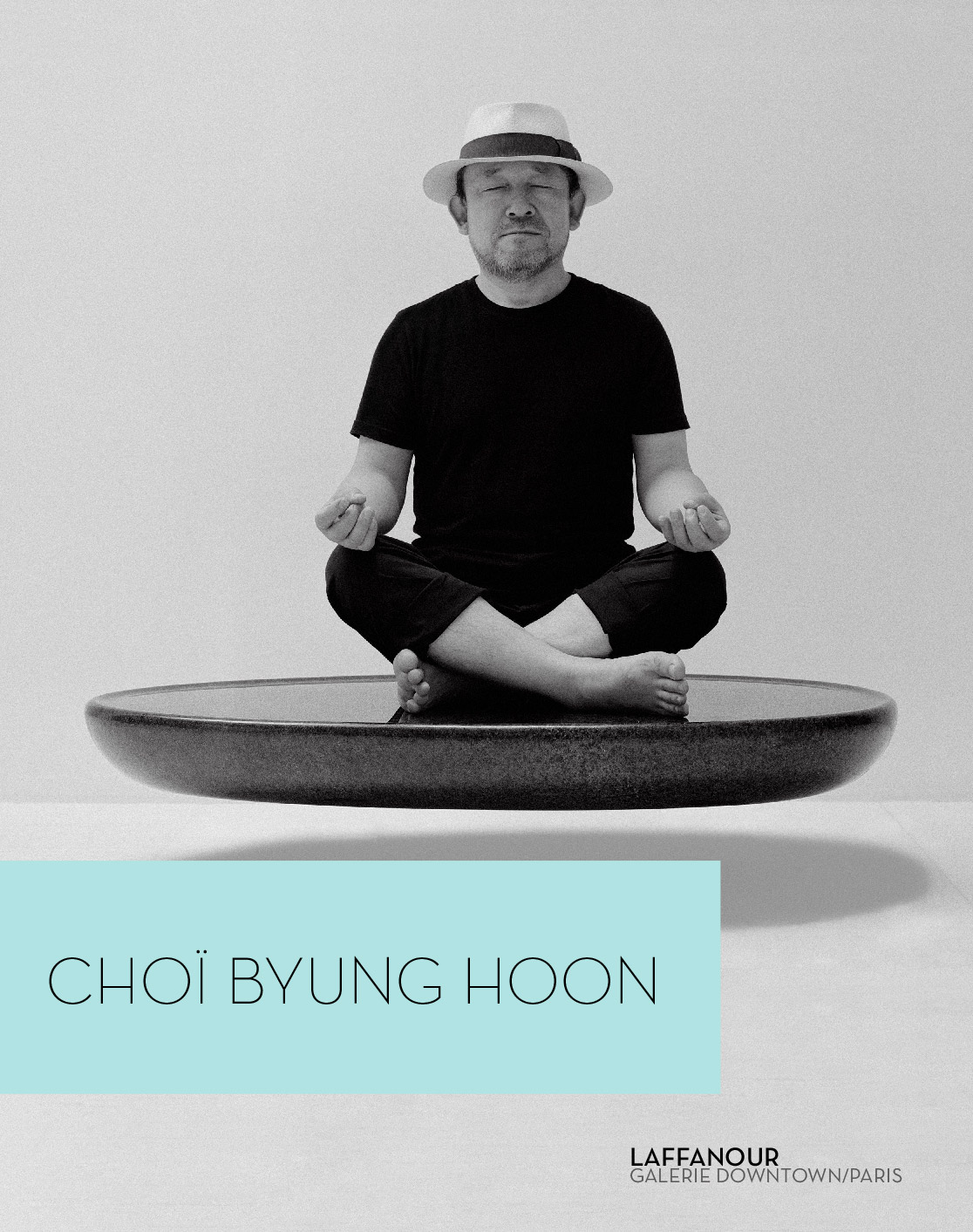

For almost 40 years, Choi Byung Hoon’s work has been illustrating this vitality and this inventiveness, together with the fact that it has also freed itself from national and ancestral traditions and aspired to a fully deserved universal dimension. Interplays of balance and novel associations of forms of matter, involving objects and forms as much as possible sculptures, defying weightlessness, where wood and stone are emancipated from the laws of gravity in order to focus solely on the laws of grace, freer and more specific. We might quote a few artist’s names with which to compare them, but doing justice to a creative artist also means sometimes taking him or her for what he or she is, the artist and the artist alone, and appreciating such artists for their works, without transcribing connections and genealogies. And only clinging to the obviousness of the work, its essence which weaves the precise bond to our universal history of modernity, the history which creates a linkage between the most removed of times and geographies: and here Asia, which is so vast, has been offering a liberating key since the mid-19th century, the key to a hierarchy-less art praxis in which painting—the noble art in the West—is no more essential than ceramics, lacqueur, mother-of-pearl, work on paper, calligraphy, and furniture. When, in Choi Byung Hoon’s case, we refer to that extremely vast oeuvre somewhere between art and design, it is indeed in this aesthetic and philosophical loam that its assumes its sense, with neither hierarchy nor marginality, but in the full page of a boundary-free creation, with neither sides taken nor priorities. And this, too, is why it seems to us to be so naturally obvious today, with our contemporary eyes. Because centuries, not to say millennia, have gone before upon this path, and they are telling us and re-telling us this particular obviousness.

Over the decades, Choi Byung Hoon’s oeuvre has been revealing a formal repertory of a rare poetry, where the Spiritual in Art enchants a real and sincere rejuvenation, such as the greatest artists have been wishing for ever since Kandinsky. In an art which lets us meditate upon the intertwining of forms, the alliance of opposed and complementary forms of matter, where stone becomes an aerial punctuation, metal a comma with an unexpected graphic flexibility, and wood and ebony an organic architecture. Looking at these works, from afar and close up, in the enclosed space of a house or set in the ups and downs of a landscape, is to accept to let oneself be amazed, a lowly and refined position, by these never precarious balances, long thought about and imagined, where nothing is left to chance, neither the choice of the striped or smooth effects of a piece of marble, nor the surface of granite, be it velveteen or harsh to the touch, nor the sensual roundness of ebony. Each work has an original strength, something sacred and earthly. Vents au début du monde/Winds at the Beginning of the World, to borrow the title of a series of furniture sculptures which, since their first presentation, seduced the world of art lovers. A visual strength which imbues them in the minds of those who have seen them, persistent images.

Since the initial preparatory tasks for the recent exhibition Korea Now! at the Museum of Decorative Arts, it seemed to us crucial to give pride of place to the work of Choi Byung Hoon, and two of his works welcomed visitors when they entered the museum’s nave. A table and a chair, made in 2008, in the series Afterimage. During the very first days of the show, Choi Byung Hoon and François Laffanour told me about their desire to offer one of his pieces to the museum, and it will join the collections within a few weeks. The admission of a new work in the collections of a museum—especially when the museum was founded more than 150 years ago to encourage creation and nurture artists’ imaginations—is always an adventure per se, a special moment, because it attests to a day and age, an art movement, and the specific nature of a creative career; and because it can display, teach and enlighten; it can also create reflection and enthusiasm about a vocation. With Choi Byung Hoon, it also rediscovers its ancient and vital brief—becoming the stuff of our dreams.

Olivier Gabet

Director of the Museums of Decorative Arts, Paris.